Harmony’s Networking Story

April 06, 2019

At Harmony, we don’t just look at what is needed to get the job done today — we want to build something that will get the job done even years from now. This goes for all layers of our technology stack, not just the higher layers closer to our key deliverables—such as smart contracts and consensus—but also lower-level, “mundane” areas such as systems and networking that others tend to take for granted.

We do this because we have a strong conviction that the key attributes of our protocol and implementation are driven not just by key components but the entire vertical stack of technologies that integrate together to enable the key deliverable at different levels. If any technology layer leaves much to be desired, the overall result suffers from that. Moreover, the lower level a suboptimal component resides, the wider its blast radius is, the greater its setback becomes, and the more difficult it is to work around or mask the failure.

In this post, we are going to talk about one such low-level but critical component: Networking. We will try to keep things simple and more approachable, so if you are already a seasoned networking expert, please bear with our networking-101-style explanations.

Please note: These are our current best approaches, but as with any bleeding-edge technological front, what we end up releasing or deploying in production may significantly differ from what we are about to discuss here.

End-to-end Communication Preferred

Harmony is built upon the end-to-end principle, which recommends that as much of the key logic of an application protocol as possible be pushed toward the end nodes that talk to one another. Nodes are self-contained and do not use middleboxes to communicate messages to other nodes, except in a few cases. Specifically, a node does not send a unicast message to another node over a multi-hop path on an overlay network of other nodes.

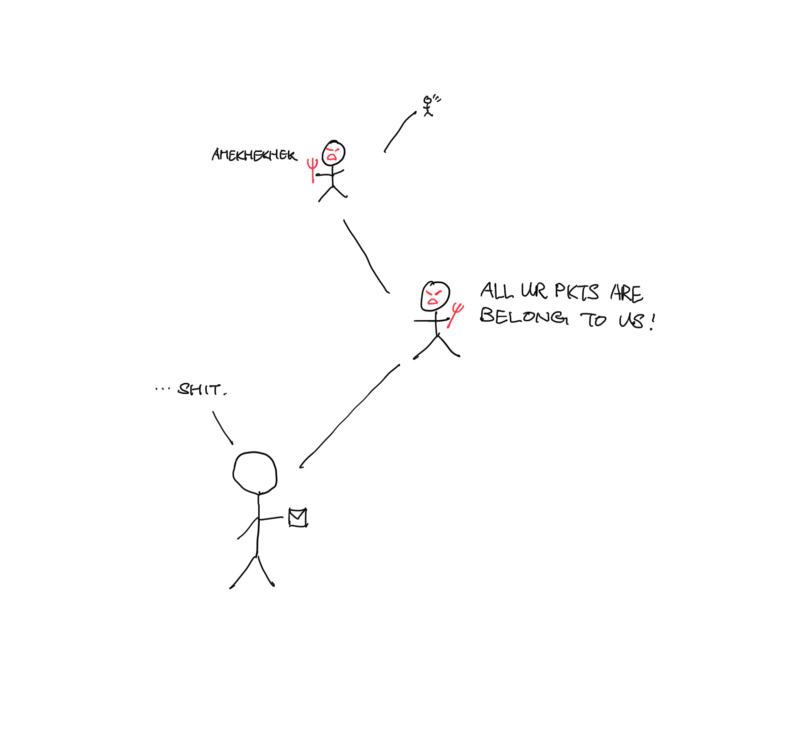

Why? Because we assume that nodes may be corrupt with a relatively high probability: In the blockchain space, we routinely talk about as few as 67% or even 50% of nodes being honest! Let’s call this probability p. Then if a message gets sent to another node h hops away, the overall probability the unicast message reaching an honest recipient p^h. For one-hop, direct end-to-end transmission, the probability of a node reaching the honest node is 67% or 50%; for two hops, 44% or 25%; for three hops; 30% or 12.5%. The probability diminishes exponentially!

Unicast messaging over multi-hop P2P overlay with adversaries

The exceptions to this principle include:

- When discovering other nodes;

- When multicasting a message; and

- When the limitation in the network topology prohibits direct communication between the sender and the recipient, e.g. due to network address translators (NAT) or network firewalls.

HIPv2: Id/Loc, Discovery, Mobility, Multi-homing, NAT Traversal

Under the end-to-end model, one major problem needs to be solved: If node A needs to talk directly to another node B without having a default go-to node, how can A discover B and find out where B lives? Let’s examine this problem deeper and see how we solve it.

Each networking entity, such as a host or a node, has two kinds of information associated with it:

- An identifier is a unique piece of information that distinguishes the associated entity from other entities on the network;

- A locator is a piece of information that the network can use to direct traffic to the associated entity.

The early Internet consisted of relatively stable, long-running hosts each holding one statically assigned IP address, which served both as the identifier and as the locator of the host, and many application protocols were built upon this assumption of one-to-one mapping between hosts and IP addresses. However, mobile and multi-homed networking, as well as the exhaustion of IPv4 address space and the resulting need to allocate IP address dynamicallybroke this one-to-one assumption on the global Internet, and brought the need for separation of identifiers from locators and for a protocol that manages the mapping between the two.

The end-to-end principle requires separation of who the sender/receiver are versus where they can be reached.

In the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), protocols such as HIPv2, ILNP, and LISP—no, not the functional programming language—have been proposed to separate the identifier and locator space, each proposal with different characteristics and use cases. Of these, HIPv2, or Host Identity Protocol Version 2, comes the closest to the use case of end nodes identified by cryptographic public-private key pairs, which directly fits the node model of the vast majority of blockchain technologies, including Harmony.

As an identifier/locator separation protocol, HIPv2 also provides support for mobility and multi-homing. Mobility support makes it possible to maintain an existing communication channel binding between two nodes despite IP address changes on one or both sides, which happens frequently for mobile nodes which can hop frequently between WiFi and cellular data. Multi-homing support makes it possible for a node to be reachable at and use more than one IP address, which can aid IPv4/IPv6 dual-stacked deployments.

HIPv2 also provides an extension for basic NAT traversal, based upon another standards-track technology named Interactive Connectivity Establishment, in order to enable most nodes hidden behind NAT to establish communication channels to each other, further supporting our end-to-end principle.

Harmony uses HIPv2 for id/loc, discovery, mobility, multihoming, and NAT traversal.

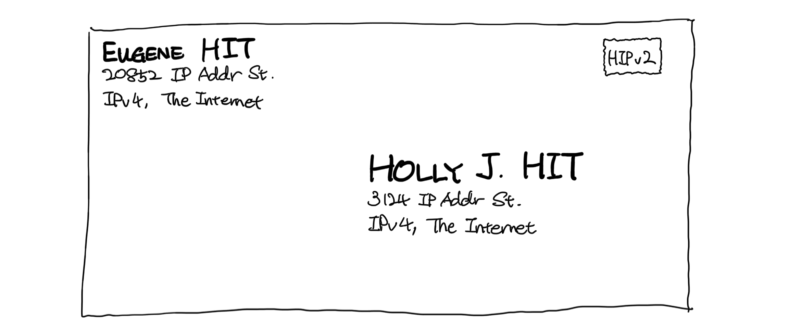

HIPv2 acts as a layer-3.5 protocol, and presents the transport layer with pseudo IP addresses named Host Identity Tags (HITs). Applications use HITs to communicate to each other, then HIPv2 handles translation between HITs and their underlying IP addresses using DNS and rendezvous mechanisms. We are also developing a DHT-based discovery mechanism on top of HIPv2, which will primarily be used to locate nodes that are unpublished and do not trust any rendezvous mechanisms.

Host Identity Tags (HITs) versus IP addresses, in HIPv2

Use of HIPv2 keeps the Harmony protocol lean, obviating the need to resolve node identifier (public key) into IP addresses.

RaptorQ: Reliable, Efficient Multicast/Unicast

Now that we have solved the who and where problems of communication, we shift our discussion to the what problem — the messages themselves. Notably, let’s examine these two real problems:

- How do we fight packet drops and corruptions so as to deliver a message reliably?

- How do we reliably deliver a multi-recipient message to its N recipients, without having its sender bear the cost of sending messages N times?

The first problem is typically solved by incorporating NAKs (negative acknowledgements, or “I didn’t get that, say it again?” signals) into the protocol. This model has two issues: 1) Such NAKs and resulting retransmissions introduce additional delays on the order of round-trip times (RTT) between the sender and the recipient, and 2) it is not easily scalable in the case of one-to-many messaging.

The second problem is typically solved by gossiping: Sending not the entire message but a chunk of it to each recipient, and requiring the recipient to relay the chunk to all the other recipients. This way, the overall cost of “sharing” such a message is evenly distributed among the sender and all the recipients.

Since the gossiping model deviates from the end-to-end principle, a new problem arises: What if some of the recipients could be faulty? What if they are uncooperative and instead keep the received chunk to themselves? RapidChain proposes an information dispersal algorithm (IDA) inspired by earlier research. It uses a combination of Reed-Solomon error correction and Merkle trees to implement secure, reliable multicasting of a large message among at least all cooperative peers, if not all peers.

Error correction codes are useful not just for the second multicast problem, but also for the first faulty path problem, such as combatting network-layer failures like packet losses.

Error correction codes can fight both problems of packet loss and load-balanced multicast.

However, Reed-Solomon code has a fixed code rate, which makes it harder to use for random packet drops. This means that if a message fragment is lost, the sender has no way of knowing which one was lost unless the receiver tells the sender. Again, such receiver-to-sender NAKs and retransmit requests slow down the protocol, especially over a high-latency, low-bandwidth connection (such as on a cellular network) where packet drops are more frequently seen.

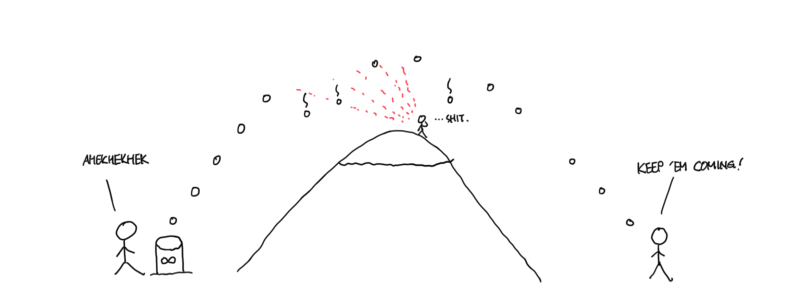

The IP broadcast industry recognized this problem from early on. In fact, in some cases, the reverse channel for NAK transmission may not even be available, or if it is, it may be much slower, in cases such as satellite broadcasting. So they turned their attention to a strategy combining forward error correction with rateless erasure codes. Unlike a fixed-rate code where there can be only a finite number of error recovery blocks, a rateless erasure code makes it possible for the sender to generate an infinite number of error recovery blocks. (This infinite generation of recovery blocks also gives rateless erasure code another name: “Fountain code.”) Because of this, when the sender of a message does not have confirmation that all necessary recipients—such as a consensus quorum—received and processed the message, it does not have to worry about which of the packets it has sent out was lost: It can simply generate more recovery blocks from the fountain and send it out, until it receives the necessary confirmation (or until it hits a protocol timeout, in the case of a synchronous protocol).

Fountain code: Infinitely many carrier pigeons born out of a “fountain”

After receiving enough error recovery blocks encoded using a rateless erasure code, regardless which blocks they are, the recipient can reconstruct the original message with very high probability. A rateless erasure code can be constructed with specific target threshold of the number of messages. Good rateless erasure codes also exhibit a phenomenon called cliff effect, which renders the probability of recovering the original message close to 1 when the recipient receives over the target threshold of error recovery blocks.

Most rateless erasure codes—such as this, this, this, and this—are similar in relying upon encoding using an XOR-based bipartite graph and belief propagation decoding, and achieve near-optimal coding efficiency. Of these, Harmony uses the state-of-the-art RaptorQ code. This IETF-standardized code has been authored by prominent engineers from companies such as Qualcomm (hi wireless) and Netflix (hi IPTV), which attests to its practical nature.

Harmony uses the RaptorQ fountain code, for reliable and load-balanced message passing.

Given n overall destination nodes of which k may be corrupt, we construct a code of a target rate such that receiving n - k - Cp encoded blocks of the message is sufficient to recover the original message. (We talk about Cpbelow.) Then, we send out n encoded blocks using this code, each block to each of the n peers. Peers gossip the encoded block that they receive to other peers, same as in the RapidChain IDA. Assuming k nodes are uncooperative and do not gossip their recovery blocks to other peers, honest nodes will still receive n-k recovery blocks, which are sufficient to reconstruct the original message.

After sending the initial burst of n encoded blocks, the sender sporadically generates additional encoded blocks and distributes them to random peers. The recommended delay is half the average round-trip time among nodes (RTT), which can be either configured statically or measured dynamically, with exponential backoff with a low base. The sender can stop generating and sending additional blocks once it confirms that all the necessary recipients (e.g. the quorum of n-k) have reconstructed and processed the original message.

The pessimist constant Cp, a small positive integer, deals with the tiny but non-zero probability that, after receiving the exact threshold number of encoded blocks, the receivers cannot still reconstruct the original message. It can also account for the baseline packet loss.

The sender signs the encoded blocks that it generates and sends. This is used in place of a Merkle tree, so that a recipient can validate the block before gossiping it to other peers. We do not use a Merkle tree here because it is hard to use for a potentially unbounded number of nodes—encoded blocks out of the “fountain”—in the tree without sacrificing its security properties.

The unicast case is similar to multicast, except:

- The number of encoded blocks and the target code rate are not governed by the consensus parameter but only by the anticipated packet loss rate;

- All encoded blocks are directly sent to the recipient;

- Encoded blocks need not be signed by the sender, because the ESPtransport employed in the underlying HIPv2 layer already offers integrity protection of the end-to-end unicast between the sender and the recipient, and the received message, being a unicast message, does not need to be relayed to other peers.

UDP Transport, With DCCP/QUIC-inspired Congestion Control

Many, if not most, blockchain protocols use TCP as their transport. However, the fully-serialized, byte-oriented nature of TCP suffers from head-of-line blocking problems and other undesirable performance drawbacks. Moreover, we realize a lot of benefits offered by TCP via other means:

- Forward error correction by RaptorQ already provides a means of reliable transmission with little latency jitter.

- Error correction block reordering is a non-issue in rateless erasure codes.

- The consensus layer protocol messages already contain generation markers such as block numbers, so reordering of protocol messages can be detected and handled by the consensus layer. The ESP data plane embedded in the HIPv2 layer handles packet corruption by HMAC.

Together, these mostly obviate the need for TCP. Therefore, Harmony departs from using TCP, and uses plain UDP as the base transport, on top of HIPv2 and ESP.

Harmony uses UDP as the base transport.

Use of plain datagram such as UDP leaves one issue still open: Congestion control. The Internet is a shared resource, and our traffic is multiplexed with countless other network flows on the same link. If the sender can detect that the path to the destination is congested (and packets are getting dropped), the sender would better back off and slow down the rate of transmission, so as to achieve good throughput economy. In other words, the ratio of effective bandwidth to the actual transmission rate should be close to 1.

Congestion control is also important in guaranteeing fair use of a shared link. In fact, the IETF FEC Building Block standard, which underlies RaptorQ, requires that a protocol that uses an FEC building block employ a congestion control mechanism, so that the content distribution protocol that uses FEC building blocks may remain a good citizen by not spamming the shared link with an unnecessarily high number of encoded blocks.

There have been multiple attempts to implement congestion control over plain datagram protocols such as UDP. Datagram Congestion Control Protocol (DCCP), a long-time IETF proposed standard, offers a means of congestion control. It has a few modes, named TCP-like and TCP-friendly, with different backoff characteristics. It is implemented in both Linux and FreeBSD.

QUIC, another transport protocol based upon UDP developed by Google and implemented in Chrome, also takes congestion control into its own hands, and implements a modern congestion control. It offers much better tolerance against lost packets in terms of bandwidth, but tends to disadvantage (“starve”) TCP sessions on the same link.

We are actively evaluating these different congestion control approaches, and will likely use one of them in the base Harmony protocol.

Harmony will implement DCCP or QUIC congestion control.

Conclusion

This concludes a brief tour around the networking technologies upon which we base our Harmony protocol. Many of you would have noticed by now that this overview does not present a novel, six-page invention complete with fancy mathematical formula or in-depth reasoning, but is rather a combination of existing technologies, some of which even a decade or more old. Not so exciting, one might say.

That is a correct observation, and actually there is a reason: Here at Harmony, we believe in pragmatism. We believe in standing on the shoulders of giants, just as most others in the world of blockchain and consensus protocols do. The most practical solution need not be the most novel ones. In fact, it is quite the opposite.

At Harmony we believe in pragmatism and past wisdom.

Take Google’s datacenter networking fabric as an example. It is a novel application of this thing called Clos network, whose root extends all the way back to the days where telephone network consisted of a criss-cross jungle of clunky electromechanical switches. As those giant monstrosities fell out of favor, so did Clos network as well. However, Google rediscovered Clos network when it was looking for a viable datacenter network design in order to handle a huge amount of east-west network traffic; lo and behold, Clos network lives again, this time in the field of modern, packet-switched networks.

The Internet is not exactly a “new thing” either. Since its inception in mid-70s, a great deal of research and development has gone into it in order to make it one of the most successful innovations of the last 50 years. Not all of those R&D results saw their heyday. Some failed to gain meaningful momentum or traction; others had their application limited to a fairly narrow field. Despite those outcomes, however, the brilliance, novelty, and elegance of these older inventions still persist, waiting to be discovered by people with matching needs.

At Harmony, we believe in this too, and aim to find promising building blocks—not just in the present day, but also in the historical archive of Internet technologies, just as Google discovered this French telephone engineer and his 70-year-old invention.

Thanks to Sahil Dewan and Nick White.