Block Syncing in 1.36s with Harmony’s Adaptive IDA Protocol

November 16, 2018

The results from our first networking benchmark are out! Eugene and Chao, two of our Amazon veterans turned Harmony networking specialists, have delivered a core component of our networking stack called Adaptive Information Dispersal Algorithm (IDA).

Our Adaptive IDA tackles a challenge central to any blockchain protocol — propagating blocks across a faulty, byzantine network — with stunning speed. Equally exciting, we will open-source this component as part of our larger peer-to-peer, end-to-end networking library “libunison”.

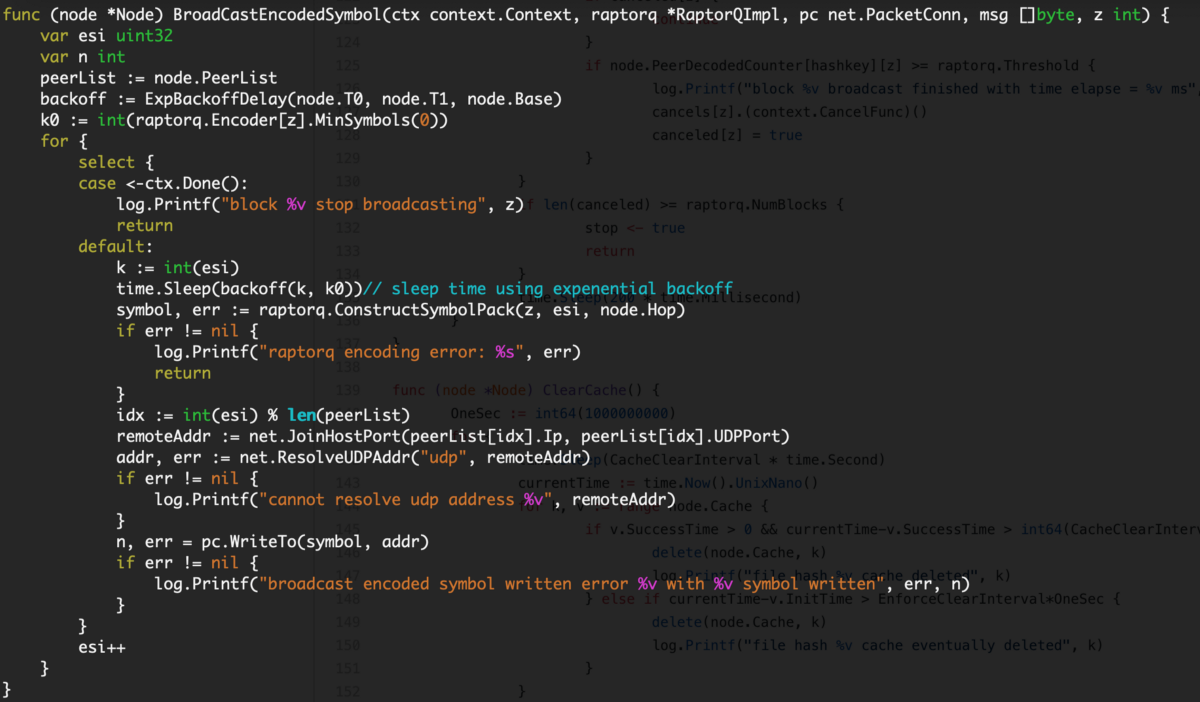

A code snippet from a core function in our Adaptive IDA library.

A bit of background

At Harmony, our goal is to build a high-performance blockchain protocol to power the next generation of decentralized applications. Our approach to achieving scalability is to build a sharded blockchain, which is optimized over all layers of the technology stack, from consensus mechanisms to systems and most important for this post, networking.

To date, the networking layer has not received the attention that it deserves in discussions around blockchain scaling. This oversight represents a huge opportunity for improvement over current protocol implementations. That’s why our team of senior engineers is eager to bring the latest techniques from the networking industry to Harmony. The remainder of this post will focus on one specific component of our networking design (IDA) but if you are interested to learn more about our general networking vision, you are encouraged to read our previous post “Harmony’s Networking Story”.

What makes networking important to blockchain?

A blockchain is in essence a replicated database that is coordinated across a network of computers over the Internet. As simple as this sounds, doing this in a permissionless and _trustless _manner is an enormous challenge.

It is not sufficient to simply send all the transactions around to all the nodes in the network, the nodes must also come to consensus on the order of these transactions so that everyone is on the same page. This last part requires a lot of communication, and that’s where networking comes in.

One of the major bottlenecks of coming to consensus is propagating the latest block of transactions from the block proposer to all network participants. Assuming a block size of 1MB and 500 participants, you are faced with the task of sending a total of 500MB of data around the network so everyone has a copy of the block. This is the fundamental problem of information dispersal and depending on how you solve it, this process can take a long time_. _The longer it takes to disseminate the block, the longer the delay between blocks which in turn means slower transaction latency and less throughput.

Block propagation techniques

Let’s explore the most naive approach to block propagation called manycast. In manycast, the block proposer sends the 1MB block to each node in the network one by one. Since the proposer has to send all 500MB himself, if he has an average broadband internet speed of 64Mbps, this would take roughly 62.5 seconds. That’s faster than Bitcoin’s average 10 minute inter-block time, but it still isn’t nearly fast enough for a high-performance blockchain like Harmony.

As you can probably guess, manycast is not very practical and not widely used for a number of reasons. More popular approaches include gossiping and multicast trees. In gossiping schemes, as new nodes hear about the block, they pass it on to others in the network. This offloads some of the communication burden from the proposer to his peers and reduces the bottleneck. In multicast schemes, the network is arranged in a branching tree structure originating from the proposer. When each node receives the block it passes the message down to its children until everyone has received it.

Whereas manycast’s time for block propagation is linear in the number of nodes in the network or O(n), gossiping and multicast approaches take time that is only logarithmic in the number of nodes in the network or O(log(n)).

This is a significant improvement, but we can do even better.

The origin of IDA

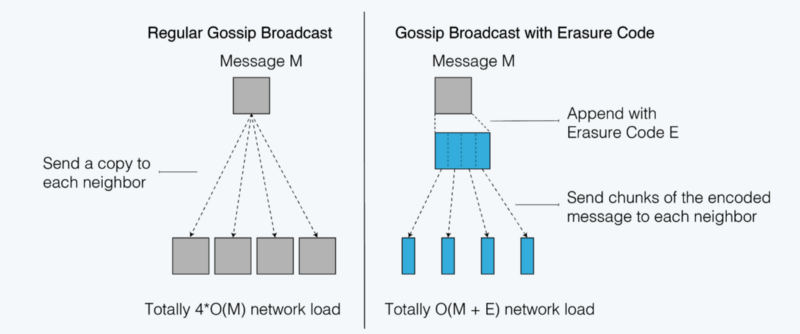

A proposal for a better block propagation scheme appeared in a 2018 paper titled Rapidchain by Zamani, Movahedi, and Raykova [1]. Among other improvements to sharded blockchain protocols, the authors propose a novel technique called — you guessed it — IDA, to disseminate a block amongst a network running a BFT consensus. The core concept behind IDA is to use erasure coding to break up a block into encoded chunks so that it can be quickly and securely spread throughout network.

To understand how IDA works, you first have to know a bit about erasure coding. Erasure coding allows you to take a piece of data and expand it into a larger encoded file. Even if portions of that encoded file are lost, the original file can still be recovered. Erasure coding schemes have _rates _which determine the amount of the encoded file that can be lost without losing the original. These rates also dictate the amount of excess data or overhead that must be encoded over the original file’s size.

In IDA, the proposer takes the 1MB block and expands it into an erasure-encoded file of 1.5MB. The proposer then chops this 1.5MB file into 500 chunks of 3kB each. Next the proposer sends one 3kB chunk to each of the 500 nodes in the network. Finally, each node in the network sends their 3kB chunk to everyone else. Then each node has the chunk it received from the proposer as well as the other 499 chunks it received from its peers. As soon as it has more than 1MB worth of 3kB chunks, that node can decode those chunks into the original block and voila we’re done!

Notice in the above example that the block proposer only sends 500 chunks of 3kB for a total 1.5MB, far less than the 500MB in the manycast example. However, each other node in the network also sends its 3kB chunk 500 times for a total of 1.5MB, making the total data transmitted 750MB. On the surface this may appear worse than manycast. The advantage of IDA is that even though more data is sent in aggregate, the sending of the data is perfectly parallelized between all the nodes. This removes the bottleneck of any single node needing to send a majority of data and allows us to best utilize the aggregate bandwidth of every node in the network.

You might ask why we can’t just split up the original 1MB block without encoding it? Good question! The answer is that in any permissionless blockchain context we cannot assume that every node will cooperate. By erasure-coding the block first, we are ensured against any malicious nodes who choose not to share their piece of data. In fact, in the above example we can tolerate up to 33% of nodes not sharing and still the rest of the nodes will be able to recover the original block. Without encoding, just one malicious node would stop every other node from recovering the entire block.

Adaptive IDA

The benefits of IDA are astonishing. By parallelizing the communication load, IDA completes in the amount of time it takes for one node to send an amount of data as large as the block plus some overhead. This further reduces the problem from logarithmic complexity to** constant complexity** or O(1).

The benefits of IDA for block propagation were immediately clear to us, but as we continued to ponder the problem, an even better solution came to our minds. Having spent 15 years working on networking protocols at NTT (Japan’s largest telco), Eugene is up to date on the latest and greatest in the networking field. The idea came from a novel application of erasure coding called RaptorQ Forward Error Correction which Eugene had designated as part of our peer-to-peer, end-to-end networking stack.

While contemplating IDA and RaptorQ FEC side by side, it dawned on us that we could use RaptorQ coding to improve IDA. RaptorQ code is a special type of erasure coding scheme called a fountain code. Fountain codes are ratelessmeaning that the encoded file has no fixed size. They are useful because they enable the person sending the original file to keep generating new encoded chunks on demand, indefinitely. The sender can act as a fountain of new encoded chunks, hence the name.

What does this have to do with IDA? In normal IDA, the code rate must be set in advance. So, assuming a 33% threat model as in PBFT, the encoded block must be at least 1.5MB to guarantee that all the honest nodes will receive the original. This implies a 50% fixed communication overhead regardless of the actual proportion of malicious nodes in the network. Anything less than 50% and block propagation could be stalled, forcing the proposer to start over.

RaptorQ’s rateless coding allows us to overcome this fixed overhead and instead adapt our code rate to actual network conditions.

To see how this would work, let’s imagine the block proposer felt optimistic about his peers and only made 1.2MB worth of chunks. This 1.2MB was split into 500 chunks and sent around the network as in normal IDA. If more than 5/6th of the network is honest, then each of the honest nodes will receive the enough chunks to make up 1MB and recover the original block. Everyone is okay and in fact the proposer has saved 0.3MB of excess overhead! However, if more than 1/6th are malicious then no honest node will be able to recover the block.

In such a situation, if we had used normal erasure coding, we could figure out which chunks had not been propagated by malicious nodes and rebroadcast them but to do so would be time consuming. Or we could restart the whole process with a higher code-rate to protect against the bad guys. Either way, consensus would get stuck and we would lose precious time.

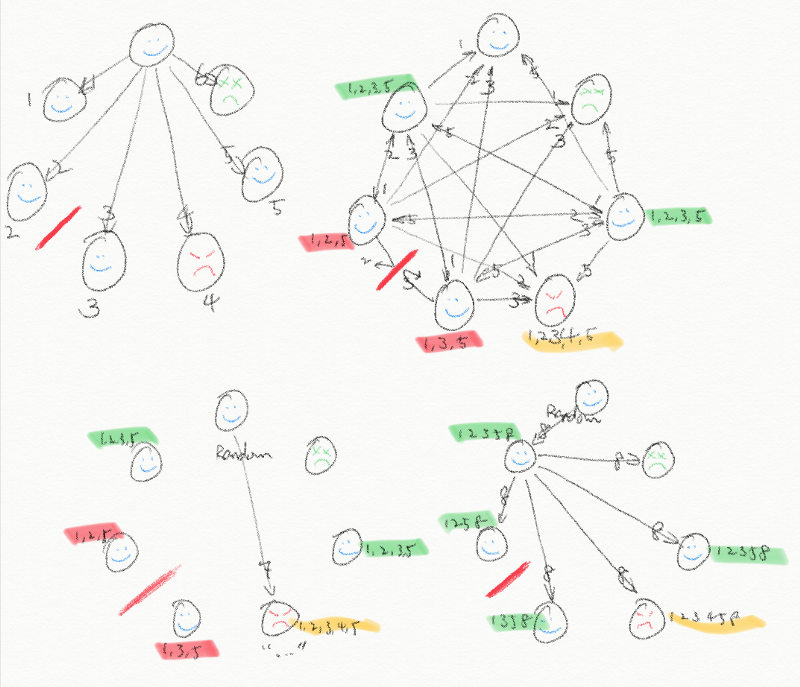

With a rateless code, the solution is much more elegant. The proposer can simply begin broadcasting entirely new chunks out of his fountain until honest nodes have received enough chunks to recover the original block. Then having learned that the initial code rate was too low, the proposer would adapt the code rate to be higher for the next round, hence the name Adaptive IDA.

Eugene’s diagram of Adaptive IDA at work. When not enough chunks reach two of the honest participants, the leader begins generating and sending new chunks until they have received enough to recover the block.

So, Adaptive IDA actually protects against more than just malicious nodes — it also protects against faulty network conditions. The Internet is unpredictable. Connections drop from time to time. You’ve no doubt experienced this frustration yourself. But no matter how unreliable the underlying Internet is, Harmony needs to be 100% reliable. Adaptive IDA handles situations in which connections between honest nodes are dropped.

Therefore, as opposed to normal IDA with fixed rate codes, Adaptive IDA can optimize the code rate for the given malicious ratio and underlying network conditions. This reduces the communication overhead and provides for quick recovery from adverse situations, making the IDA process even faster and more resilient.

Bonus: For those network geeks out there, you could consider Adaptive IDA as a block propagation analog of adaptive window connections in TCP.

Whitepaper

If you found this post interesting, you should check out our recently released technical whitepaper. In it you’ll find lots of novel approaches like this one for scaling consensus as we endeavor to deliver a high-performance blockchain protocol to power the next generation of decentralized applications.

Open Source

We’re proud of what we’ve built and our implementation of Adaptive IDA is open source for anyone to use. Please head over to our github and dig around in the code! This is one part of our larger effort to release a full P2P, E2E networking library called libunison. We hope that our our open-source networking software contributions will drive the entire blockchain ecosystem forward.

Discord

If you want to get in touch with us, we are very active on Discord and welcome you to join our channel and get to know us. You can watch our open development in progress!

Research Forum

If you found this interesting, please check out our research forum where we talk about many more ideas like these. If you want a more mathematical and technical explanation of Adaptive IDA, make a new topic in the networking category of the forum. Come discuss!

Special thanks to Arunesh Mishra from Picolo Labs for his feedback on this post.

[1] M. Zamani, M. Movahedi, and M. Raykova, “RapidChain: A Fast Blockchain Protocol via Full Sharding.” Cryptology ePrint Archive, Report 2018/460, 2018. https://eprint.iacr.org/2018/460.